-

Glucose Monitoring

Glucose Meters (BGM) & Monitoring

-

Insulin Delivery

Find & Compare Insulin Pumps & Delivery Devices

View current insulin pumps, smart pens and more from a variety of manufacturers. Compare features and technical specifications and find training resources, affordability information, prescription details and more.

Find Infusion Sets

View features and specifications of popular infusion sets to determine the best option for your patients and clients.

Open-Source AID

Open-source AID systems like Loop, AndroidAPS, and Trio combine pumps, CGMs, and smartphone apps to deliver customizable insulin automation. This section explains how they work, their unique features, safety considerations, and how clinicians can support patients using these evolving tools.

-

Medicines & Therapies

Find & Compare Delivery Devices

View and compare features and technical specifications for current traditional pens, connected pens, inhaled options and patches for insulins, glucagon and other medicines to help manage diabetes.

Basal Insulin Initiation & Titration

Proper basal insulin initiation and titration can help reduce therapeutic inertia and engage patients in their diabetes management. Find videos, podcasts and other resources to fine tune your knowledge.

-

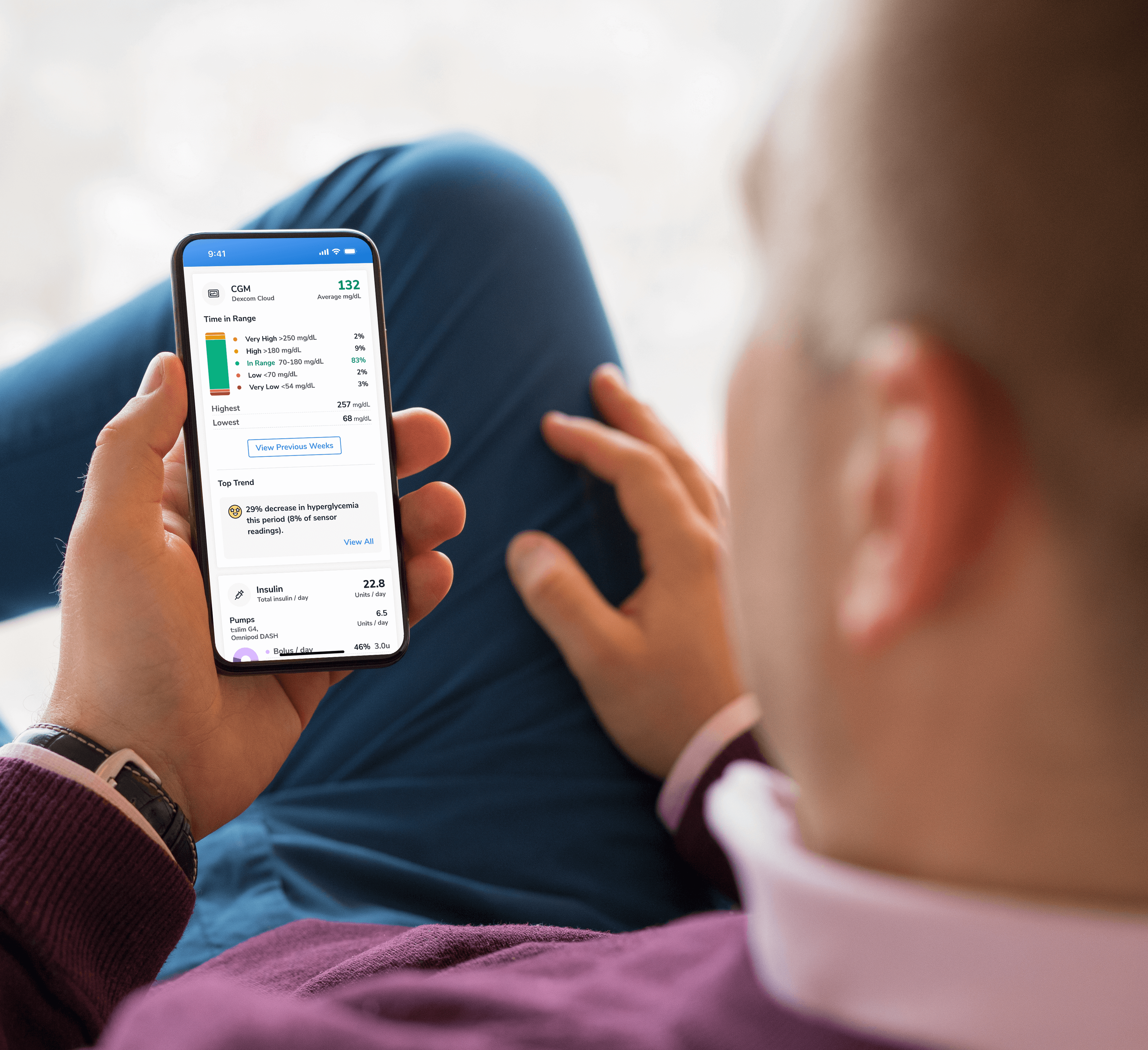

Apps & Platforms

Find Apps & Platforms

Find a sample of the latest online apps and digital platforms designed to prevent, manage and/or treat diabetes. We highlight apps and DTx for people with diabetes as well as the professionals treating them.

Glycemic Management

An overview of Glycemic Management Platforms that answers key questions including: What are they? What to consider? How can my inpatient facility benefit and more.

Intro to Digital Ordering & Authorization Platforms

Are prior authorizations delaying patient care? Is your team overwhelmed by manual workflows? These platforms might help.

-

Education & Training

Online Learning

Find diabetes certificate programs, online learning opportunities, webinars, device training, practical tools and more. All resources are developed for diabetes healthcare professionals by diabetes healthcare professionals.

Podcasts & Videos

Find a variety of podcasts and videos focused on the latest topics in diabetes technology specifically created for diabetes healthcare professionals.

Diabetes Device Training

Danatech device trainings introduce healthcare professionals to the latest diabetes technology including the newest CGMs, automated insulin delivery devices, smart pens and more. Trainings include overviews, training specifics, FAQs and more.

Diabetes Tech Coding & Reimbursement

Coding, billing and reimbursement information for wearable CGMs, implantable CGMs, AID training and more.

Diabetes Technology Conference

The only event designed by and for the care team focused on using technology in practice to improve outcomes for people with diabetes.

-

Explore

Cardiometabolic Health Resources

Help tackle cardiovascular issues by equipping yourself with the knowledge to reduce cardiometabolic risk and combat the development of cardiometabolic diseases with specialized education and resources from danatech.

T1D Screening Guide

Find key points on T1D screening, including how to discuss screening with clients and families, psychosocial and health equity aspects of screening and heightening awareness about T1D as a pre-clinical autoimmune disease.

Guide to Becoming a CDCES

Whether you’re a healthcare professional seeking to enhance your expertise or someone passionate about making a significant impact in the lives of those affected by diabetes, this guide will help you navigate the path to becoming a CDCES.

Spinal Cord Stimulation for DPN

Discover how spinal cord stimulation (SCS) using electrodes implanted near the spinal cord deliver electrical pulses that disrupt pain signals traveling to the brain and improve quality of life for patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN).

News & Perspectives in Diabetes Tech

Recent diabetes technology innovations, product launches and enhancements as well as clinical perspectives regarding diabetes care.

Support Legislation

Make your voice heard on Capitol Hill by sending messages to your members of Congress on critical issues that affect diabetes care and education. You can also track federal diabetes legislation to see which members have signed on to support the bill and whether there have been any relevant votes.

-(1).png?sfvrsn=799e9a59_1)