The Emotional Impact of T1D Screening in Clinical Settings

Risk screening for Type 1 diabetes (T1D) using diabetes-associated

autoantibodies testing has been conducted in research for some time. However,

such factors as the increasing availability of commercial methods for this

screening, plus pharmacological advances in potentially delaying the onset of

T1D in at-risk individuals, are leading to more focus on T1D-risk screening in

clinical settings.

As clinical T1D screening becomes more common, Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (DCESs) and other health care professionals (HCPs) must be prepared to address the potential psychosocial

consequences of a positive autoantibody testing result.

Receiving a positive autoantibody test result can be stressful because T1D

is unpredictable — there is some uncertainty as to whether or when the person

will develop T1D, and T1D is not currently preventable.

The risk of T1D based on screening results varies based on the number of autoantibodies

present and the persistence of the autoantibody, so an individual may have

different reactions to their screening results based on this information.

For example, among children with no family history of T1D, those positive

for a single, persistent autoantibody have a 23% risk of developing T1D over

the next 15 years, while those with multiple autoantibodies have a 70% risk of

developing T1D over the next 15 years.

Overall, T1D risk based on autoantibody status is complex, and can vary by

the individual’s T1D-related genetic profile, family history of T1D, age at

onset of autoantibody and the type of autoantibody that is first positive. The

consequences of a T1D diagnosis are serious because T1D is a treatable but

lifelong, chronic condition.

Several large-scale research studies have examined the impacts of T1D-risk

screening on individuals and families. Lessons learned from these studies can

help anyone involved in conducting screening in a clinical setting. These

studies have highlighted the emotional impact of screening for T1D risk, which

can include heightened anxiety about T1D risk.

Over time, anxiety about T1D risk often decreases but tends to remain high

in certain groups like parents of children with multiple autoantibody-positive

results that are at the highest risk for developing T1D. In a recent study of

parents with no family history of T1D, nearly 3 in 4 parents (74.4%) of

children found to be autoantibody-positive reported significant anxiety about

their child's risk of T1D, and parents of multiple autoantibody-positive children

had the highest anxiety. Another study found that approximately 40% of mothers

and 20% of fathers reported clinically elevated symptoms of depression

following autoantibody-positive notification.

In addition to the emotional impact of screening and T1D risk, there are

documented challenges with individuals' ability to understand the risk of T1D

conferred by autoantibody positivity. For example, it is common for parents of

children at risk for T1D to underestimate their child's risk. Individuals who

are at risk may engage in behavioral changes such as altering their diet or

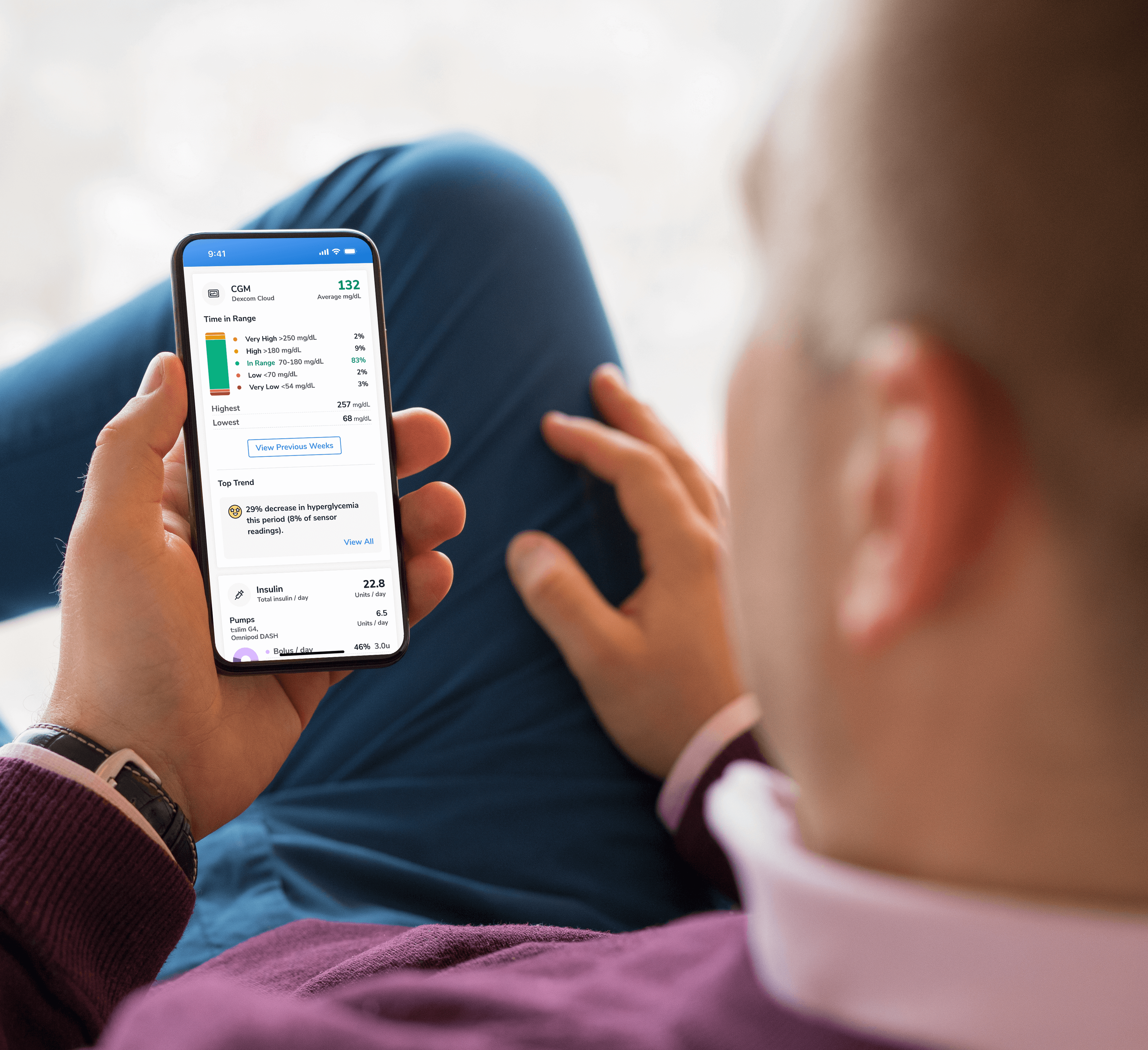

glucose monitoring to watch for disease onset.

Preparation Before Initiating a Clinical Screening Program

T1D-risk screening should not be started without having all the necessary resources in place. These resources include:

- Reliable and valid methods for initial and confirmation autoantibody testing, and how these methods will be paid.

- A monitoring plan for those who confirm as autoantibody positive and how the plan will be paid

- A plan for informing eligible participants about the risks and benefits of T1D-risk screening, plus the process of screening and its cost

- A plan for informing participants of autoantibody test results

- A plan for addressing potential psychosocial impacts in anyone who tests autoantibody positive, as well as their family members.

Pre-Screening Education

Before beginning T1D-risk screening, individuals and their families need to

understand T1D, the risk-screening process, and the next steps, plus the risks,

costs, and benefits associated with this testing.

This education process is similar to the process of informed consent in

research studies or for medical procedures. HCPs, especially DCESs, are uniquely

qualified to provide this information in a helpful and easy to understand way,

given their expertise in diabetes-focused education.

It is crucial to provide individuals and families with basic information

about T1D, to ensure they understand how T1D develops from an autoimmune

process and requires lifelong treatment including insulin administration,

glucose monitoring, and nutrition and exercise considerations.

Most important, any misconceptions about T1D — particularly any

misunderstandings related to how the disease develops or confusion with Type 2

diabetes — should be addressed.

Clinical staff should provide information about the autoantibody markers

tested (e.g., IAA, GADA, etc.) in the screening process, and that any autoantibody

positive result must be confirmed by a second test. If after an autoantibody positive

result is confirmed by a second autoantibody

positive test, this suggests the autoimmune process associated with T1D has

begun.

The individual and family must understand the steps involved in the screening process:

- Blood draw

- Awaiting results

- Need for a second confirmatory test if an initial autoantibody test is positive

It is important to ensure individuals know how screening results will be

communicated (e.g., via a phone call and follow-up appointment) and what will

happen if individuals screen negative or positive. The cost of the process and

potential insurance coverage (or not) should be explained before testing.

Benefits and Risks

The potential risks and benefits of T1D-risk screening should be thoroughly discussed as part of any individual or family's decision to undergo the screening. The benefits of screening include:

- Allowing more time to learn about and adjust to the possibility of a T1D diagnosis versus a more acute, potentially traumatic adjustment period after diagnosis without risk screening.

- Early diagnosis of T1D through screening may prevent diabetes-related ketoacidosis (DKA) which can be life threatening.

- Individuals who screen for T1D may be eligible for medical interventions to potentially delay the onset of the disease or may be eligible for clinical trials for new drugs being evaluated for their effectiveness in reducing the risk for or delaying the onset of T1D.

The potential risks of T1D-risk screenings should be discussed. Individuals should be informed that negative screening results do not guarantee that T1D will never occur, but rather suggest that the T1D autoimmune process is not currently in process. Individuals with positive results may experience anxiety or worry about developing T1D.

Further, the uncertainty regarding if and when T1D will develop can be particularly difficult for individuals and families. Additional risks for screening include the time and cost of follow-up monitoring for those who screen positive. Individuals should be aware that even if they screen positive, there is currently no method of preventing T1D.

Communicating T1D-risk Screening Results & Follow-up

Most individuals will screen negative for autoantibodies. These negative results may be communicated in person, by phone, or by mail. The communication should emphasize that a negative test means there is no active T1D autoimmune process at present. However, the communication should also state that a negative result does not guarantee that an individual will never develop T1D.

Whatever the results of the screening, be sure to provide ample opportunity to provide clarification or answer questions for individuals and their family members.

An initial positive autoantibody test result should be discussed in person, either at a clinic visit or by phone. Emphasis should be placed on the fact that an initial positive result does not mean they have an ongoing T1D autoimmune process. A second test is needed to confirm autoimmunity. The second test could be negative or positive. A participant's anxiety or worries are best addressed by ensuring the confirmation testing is done.

A second confirmed positive autoantibody test result should be discussed in person. The person should be helped to understand that an ongoing T1D autoimmune process has been detected. However, when — or even if — the individual will get diabetes is unknown. For this reason, the person needs to be monitored for the development of the disease.

The monitoring program should be fully explained and put in place. For individuals screening positive for autoantibodies (both initially and with a confirmed result), it is critical to ask about their reaction to this news. It is common to experience worry and anxiety about T1D risk, so it is important to reassure the individual that these worries are completely normal.

In some clinical settings, general screening instruments, such as those for depression and/or anxiety, may already be used (such as the Patient Health Questionnaire — PHQ-9, General Anxiety Disorder — GAD-7). While these instruments can provide useful information about an individual's general psychological functioning, they are typically not useful for assessing reactions to T1D-risk screening results and should not be used in place of directly inquiring about an individual's reaction to and coping with an autoantibody

How the individual will share this information with significant others or family members — who may also experience significant anxiety or worry in response to a confirmed autoantibody positive result — should be discussed.

For many, the monitoring program itself can help reduce the stress of knowing they are autoantibody positive, as it provides some sense of predictability about potential disease onset and a sense that medical support is available to them should a diagnosis occur.

However, check-ins about how they are feeling about the testing and their psychological functioning should be ongoing, and not limited to the time of the initial confirmed autoantibody testing. Their reactions may change over time or in response to the monitoring program results. Referral to a mental health specialist, preferably one who specializes in T1D, should always be presented as an option if needed.

It is important to recognize that some individuals cope or respond to an initial or confirmatory autoantibody positive test result by refusing further participation in testing or monitoring. These individuals may cope with the stress of a positive result by denial, or by doing their best to not think further about the situation. These individuals will not benefit from a T1D-risk screening program. A thorough discussion of the risks and benefits of T1D-risk screening as part of the individual's decision to engage in screening is one effective way of helping those who would not benefit from it to opt out of the program.

Special Considerations for Children and Families

Many individuals who present for T1D screening

will be children. Although their parents may legally decide, as their child's

guardian, whether a child should participate in T1D-risk screening,

participation by children aged 10 years and older in the process of consenting

to screening should be encouraged. At this age, children should be included in

all aspects of the preparation process, so they are fully informed. This will

require the use of age-appropriate language and regular engagement with the

child to address any confusion, misunderstandings, or questions they may have.

Many parents will permit their child to decide whether to undertake T1D-risk

screening. This is common and is an acceptable family approach to a complex

situation. If a child has a confirmed positive result, special care should be

taken to assess the child's reaction to this result in addition to that of the

child's parents. Recognize that a child's reaction to new and potentially

stressful information can be delayed, or they may have trouble expressing their

feelings or formulating questions. Regular check-ins about how they are coping

are vital to address any new reactions and/or questions that may occur.

Key Takeaways

- T1D-risk screening can provide useful information for families, but can also lead to uncertainty, misunderstanding of T1D risk, anxiety, and behavior changes intended to prevent or monitor for T1D in some individuals.

- Individuals and families should be fully informed about the benefits, costs, and steps involved in T1D-risk screening before screening is initiated.

- Health care practices that participate in T1D-risk screening should have adequate systems and support processes in place. These include a system for ordering initial and confirmatory laboratory testing and reporting the results to families, a standardized education program for informing families about the benefits and risks of screening, and mental health referral sources for those who may need additional support after learning of their screening results.

-(1).png?sfvrsn=799e9a59_1)